- Home

- PLASTA Sustainability Charter

Sustainability in Surgery

Climate change

Human activity is the main contributor to global climate change, yet paradoxically human health is set to suffer. Heat-related deaths, severe weather events and tropical disease are increasing globally, which will also exacerbate global health inequalities. Pollution creates poor air quality, which directly impacts respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

The Lancet has described climate change as the greatest threat to human health of the 21st century1. As clinicians, we have a responsibility to care about the impact of climate change on the health of our patients and have a vital role in promoting good behaviours.

The GMC have included a statement in Good medical practice 2024:

“You should choose sustainable solutions when you’re able to, provided these don’t compromise care standards. You should consider supporting initiatives to reduce the environmental impact of healthcare.”

Healthcare’s impact

The NHS is responsible for ¼ of all public sector greenhouse gas emissions, 4.4% of the country’s total emissions (as a comparison the aviation industry is responsible for 2.5%). If global healthcare were a country, it would have the same emissions as Japan.

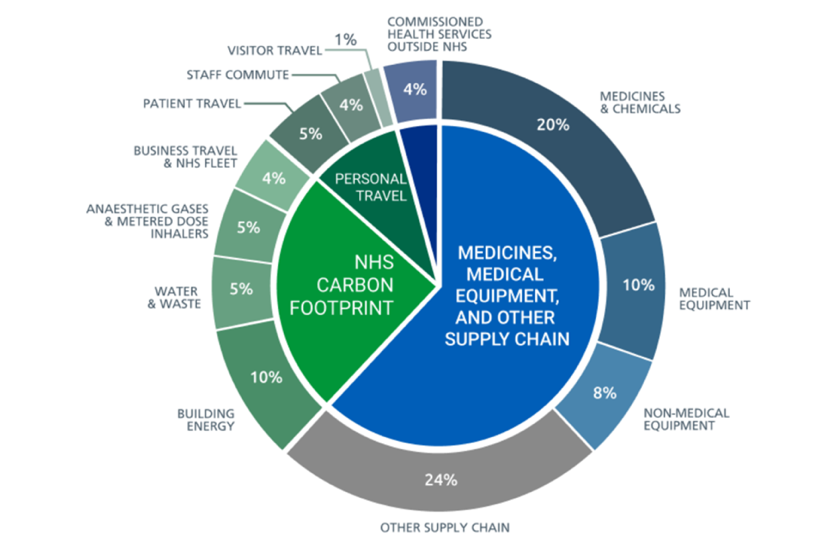

What contributes to this impact? The majority comprises of procured consumables such as equipment and medicines (see figure below). The US healthcare sector generates 1.7 million tonnes of plastic waste per year. There are also significant contributions from energy, anaesthetic gases and travel. The NHS in England is responsible for 9.5 billion road miles, which amounts to 7 285 tonnes of nitrous oxide and 330 tonnes of particulates per year. An estimated 1 in 20 journeys on UK roads are healthcare related.

Figure 1: Sources of carbon emissions by proportion of NHS Carbon Footprint Plus (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/climate-change-applying-all-our-health/climate-and-health-applying-all-our-health)

Recognising this, the NHS has pledged Net Zero emissions by 2045. As clinicians, we do not need to wait for policy change from a managerial or governmental level; it is thought that around 80% of the carbon footprint can be attributed to clinical decisions and models of care. Therefore, you can influence change now.

In Surgery

A single operation creates emissions equivalent to driving 2,273 miles driven in a petrol car2. It is a sector which uses vast quantities of single-use consumables, anaesthetic gases, and energy – so-called ‘hot-spots’. Surgery produces approximately 50-70% of total hospital waste. The anaesthetic gas desfluorane has a global warming potential 2,500 times greater than CO2, which is why it is decommissioned in the UK.

While the breakdown of emissions in individual procedures varies3, instruments, devices and consumables are responsible for the greatest share.

There are also significant labour rights abuses in the supply chains of surgical products, with most instruments being produced sweatshops in Pakistan using child labour; and forced migrant labour manufacturing gloves in Malaysia and Thailand4. Items that we take for granted and over-use in clinical practice may have caused those in less advantaged backgrounds elsewhere in the world to come to harm.

What can you do?

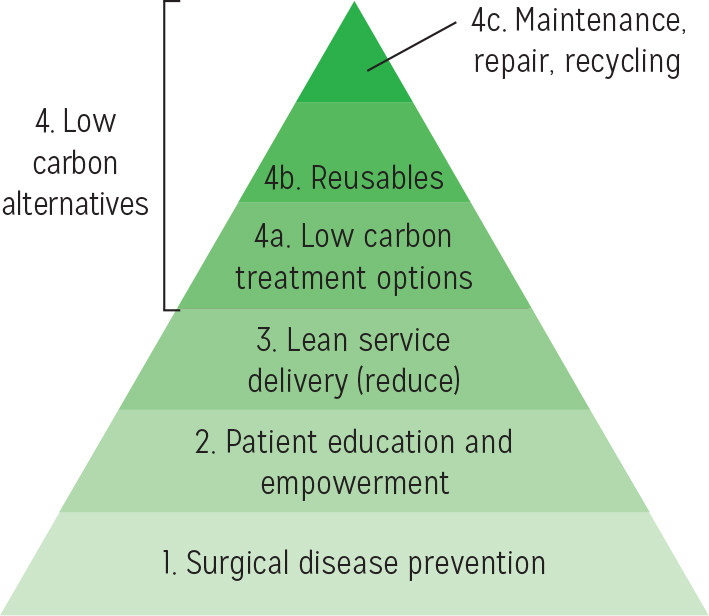

The aforementioned ‘hot spots’ can be a target for emission reduction in theatres. However, there are options to reduce emissions across the whole surgical pathway. Figure 2 represents the principles of surgical sustainability, with each layer of the pyramid representing the size of the contribution, i.e., preventing surgical disease in the first place is the most impactful intervention. You will notice that recycling is right at the top. It is a misconception that recycling is the answer to climate change; In fact, waste streams only account for around 1% of the NHS carbon footprint.

Figure 2: Principles of surgical sustainability5

You can also think about it in terms of the 5 Rs: REDUCE, REUSE, RETHINK, RECYCLE, RESEARCH.

Plastic surgery is an excellent specialty to try and reduce emissions from surgical procedures. These can be built into research or quality improvement projects. Here are some examples and ideas:

- Switch from single use items to reusable items (gowns, instruments, consumables)

- Virtual follow-up, including hand therapy, pathology results etc.

- Move minor procedures out of main theatres and into clinic procedure rooms.

- Minimise antibiotic use in line with the evidence-base.

- Promoting WALANT.

- Powering down: turning off lights, computers and HVAC systems when not in use

The Intercollegiate Green Theatre Checklist and Compendium of Evidence is an excellent resource to help plan projects and promote sustainability in your department.

Further links and information

Green Surgery Report

For A Greener NHS

How to make a sustainable quality improvement project

HealthcareLCA Database: carbon footprint analyses of healthcare activities

Relevant literature in plastic surgery

A Narrative Review of Plastic Surgery and Climate Change

Reducing the carbon footprint of hand surgery case study

Field sterility in skin and hand surgery

FEESH green survey: sustainability in hand surgery

Carbon footprint of skin cancer surgery

Carbon neutral hand surgery

References

-

Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015; 386: 1861–1914.

-

Rizan C, Steinbach I, Nicholson R et al. The carbon footprint of operating theatres: a systematic review. Ann Surg . In press

-

Robinson PN, Surendran KSB, Lim SJ, Robinson M. the carbon footprint of surgical operations: a systematic review update. RCS Annals 2023; 105 (8): 692-708.

-

Brighton & Sussex Medical School, Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, and UK Health Alliance on Climate Change (2023). Green surgery: Reducing the environmental impact of surgical care (v1.1). London: UKHACC. https://ukhealthalliance.org/sustainable-healthcare/green-surgery-report

-

Rizan C, Reed M, Mortimer F, et al. Using surgical sustainability principles to improve planetary health and optimise surgical services following the COVID-19 pandemic. The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2020; 102 (5): 177-81.

Contact the PLASTA team for further information and to share projects and ideas.